Human Rights Day With “Chinese Characteristics” – Rights Defender Ni Yulan’s Story

Posted by Author on January 29, 2011

This article was published in the South China Morning Post on December 22, 2010, under the title “Dark days and rights.” It was published in Chinese in Taiwan’s China Times on December 23, 2010. (繁体中文)Illustration from South China Morning Post.

by Jerome A. Cohen

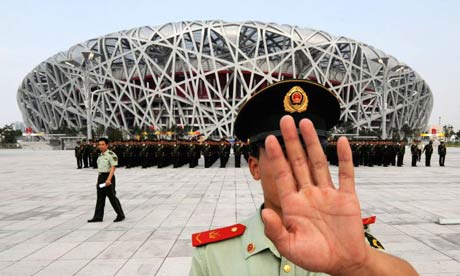

On Human Rights Day this year, the day on which imprisoned writer Liu Xiaobo was honoured with the Nobel Peace Prize in Oslo, I was in Beijing, where the authorities’ angry clampdown on dissent had brought about an eerie hush among those aware of the occasion. Scores of activists had been placed under house arrest, deprived of internet and phone services, or “vacationed” out of town to ensure their silence.

Seeking to mark the day beyond my academic meetings, I visited Ni Yulan , a courageous former lawyer who was permanently crippled by police in 2002 in retaliation for her defence of human rights. Ni first came to public attention in the summer because she and her husband had been reduced to living in a Beijing park. Thanks to overseas publicity and Emergency Shelter, independent director He Yang’s video about the couple, they now share a small room in a run-down hotel, watched and occasionally harassed by the authorities. It was there that we talked about the plight of human rights lawyers in China.

Ni chose to study law just as legal education was reviving after the Cultural Revolution. Upon graduation from the elite China University of Political Science and Law, in the mid-1980s, she became a lawyer for a government export company. It was only in 1999 that she became embroiled in human rights issues when a neighbourhood family was victimised by the brutal Communist Party campaign against the Falun Gong. First the neighbour’s mother, then the father, died in detention in circumstances that were never investigated. When no one else offered legal help in so sensitive a matter, Ni felt she could not refuse. “It was from then on that the police targeted me,” she says.

Her second human rights case involved another major issue, forced housing demolition. In April 2002, following her efforts to help neighbours facing compulsory eviction and relocation, Beijing police dragged her to a police station and tortured her expertly for many hours. “They said I was minding too many things that are not my business,” she says.

In Emergency Shelter, she recalls, `they pushed me to the ground, then they took a rope and tied me up in a sort of bundle. And after tying me

up, they pulled the rope upward. At the time I could hear a cracking sound in my ribs, and then I was in unbearable pain. I started crying … [Later, they] used their feet and their knees to press against my [lower] back, the bone gaps, the acupuncture points, the tendons and bones. They really knew how to beat people up.”

After a long detention, Ni was belatedly taken to hospital and then prosecuted for “obstructing an officer”. “I tried to hire a lawyer but they would not let me; nor would they let me appeal when I was convicted. They said I was a special case because I was opposing the government.”

She was sentenced to one year in jail. Because of her criminal conviction, her lawyer’s licence was permanently revoked. “I kept sending letters to the lawyers’ association asking them to help me, but they would just say they had not received any letter.” Worse than the loss of her profession, Ni never recovered the use of her legs.

But she never lost her determination. Released from jail in 2003, she turned all her energy to helping other victims of criminal injustice, religious persecution and forced demolition, including many petitioners who flocked to Beijing from across the country seeking relief.

Ni’s own legal problems, meanwhile, grew worse. Since her first horrific ordeal in 2002, she has fruitlessly kept applying for a retrial and government compensation for the torture it inflicted. In addition, her own substantial home was forcibly demolished in 2008. When Ni protested at the destruction of its last remaining rooms, she was beaten, suffering open wounds to her head, and again detained, together with her husband.

Ni says that, in the worst incident of that episode, officer Xiao Wei from the Xicheng district police station ordered his colleagues out of the interrogation room, and then assaulted her. “He peed in my face.” He later accused her, a disabled woman crouching on the floor, of having assaulted a police officer, and she was charged with a crime again.

The lawyer she was allowed to hire for her second criminal trial, having been intimidated, refused to enter a not-guilty plea. “So we dismissed him.” Ill and weak, Ni unsuccessfully defended herself at trial. Despite the efforts of her courageous appeal lawyer, Liu Wei, who was subsequently deprived of her own lawyer’s licence, Ni was sentenced to another prison term, this time two years.

In prison, she was treated with great cruelty. In Emergency Shelter, she says: “Because I didn’t admit guilt, they wouldn’t let me sleep at night. I wasn’t allowed to lie down and had to sit on a bench, and during the day they sent me to work. The worst was that they ordered me to crawl. I wasn’t allowed to use crutches. I wasn’t allowed to support myself using a chair. Every day I had to crawl from the upstairs cell down the stairs from the fifth floor … and then across the big prison yard. I had to crawl to the workshop, which was 500 metres away, and then up to the second floor … At midday I had to return to the cellblock to eat, and then crawl back downstairs to work. Every day, I had to make four journeys crawling back and forth.”

Even now, petitioners come to seek advice from Ni as well as to show solidarity. The day I visited was no different. The couple now depends on the charity of friends, and many come forward to help those who continue to help them. No state authority assists Ni and her husband. Yet, shortly after I left their room, still jammed with petitioners, the government did mark Human Rights Day with “Chinese characteristics” by cutting off the couple’s electricity! Typically, they lit candles and continued their work.

Jerome A. Cohen is professor and co-director of the US-Asia Law Institute at NYU School of Law and adjunct senior fellow for Asia at the Council on Foreign Relations. See www.usasialaw.org

Rate this:

Share this:

- Click to email a link to a friend (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Tumblr (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to print (Opens in new window)

Related

This entry was posted on January 29, 2011 at 10:58 pm and is filed under Activist, Beijing, China, Human Rights, Law, Lawyer, News, People, Politics, Social, World. You can follow any responses to this entry through the RSS 2.0 feed. Both comments and pings are currently closed.

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.